The Lifelong Effects of Toxic Stress Don’t Just Kill — They Torture 1st

Table of Contents

To Understand the Lifelong Effects of Toxic Stress, Let’s First Explore the 3 Types of Stress

Perhaps you’ve seen or heard this quote or a variation of it from a stranger or a loved one in your life: “You cannot suffer the past or future because they do not exist. What you are suffering is your memory and your imagination.” – Sadhguru

Presumably it’s meant to be empowering. But it fails to take into account the direct, lingering and often lifelong effects of toxic stress and it’s very real impact not just on our bodies, but on our brains. Especially children’s brains. Memory and imagination have little to do with it.

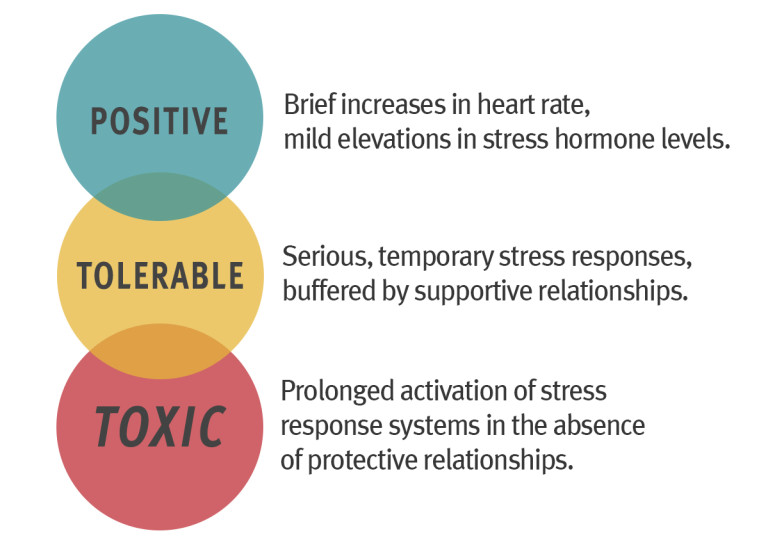

There are three basic levels of stress: positive, tolerable, and toxic.

Positive stress is moderate, short-lived, and essential to healthy development. We all experience varying levels of it throughout the day, and it drives performance. It gets us going in the morning; it gives us a list of things to do; it assigns priorities and helps us to engage in behavior that’s important to survival and development. Typical stressors that children face — making new friends, starting daycare or preschool, welcoming a new baby sibling into the family — are beneficial to development, under the right circumstances.

Typical stressors that are considered positive for adults include- a big project or assignment at work or school, starting a new job, learning a hobby. Positive stress, may sometimes be called “good stress” because stress truly is vital for a healthy life. To put it briefly, this type of stress will always be short-term and it should inspire or motivate you because there should always be an end in sight (I.e., a project due date, a new job start date, etc.).

Tolerable stress is deeper and longer-lasting, the kind often associated with sudden or impending loss—death, illness, accidents, divorce, unemployment. For children, tolerable stress may also include events like an injury or a natural disaster. Most of us are fortunate enough to have family, friends, and colleagues we can turn to for support. Just knowing that someone is there to care for us, hug us, and listen to us, helps us get through the darkest days following the event and sets us on a course to recover and to function normally, despite memories of the loss or stressor.

Unlike tolerable stress, the lifelong effects of toxic stress do not allow us to function normally or to fully recover as we would from tolerable and positive stress. Toxic stress is overwhelming and can have a lasting impact on our physical and mental-wellbeing. Unlike tolerable stress, toxic stress can disrupt our brain development, impair cognitive function, and increase the risk of health issues such as heart disease, mental health disorders, and even diabetes.

The Lifelong Effects of Toxic Stress: What is it and Where Does it Start?

Toxic stress results from two sets of conditions: a) a severe, ongoing situation like abuse (physical, emotional, or sexual); neglect (physical or emotional); household dysfunction (substance use, mental illness, divorce, abuse of mother) or combinations of such circumstances; and b), a lack of relationships that could provide support for the sufferer.

After experiencing positive and tolerable stress, a person can return to baseline. After toxic stress, the baseline is changed. Toxic stress changes the way the brain functions—not just psychologically but biologically, at the level we often refer to as “hardwiring”—and those changes may be permanent without intervention. The lifelong effects of toxic stress alter what our baseline level is, and therefore continue to torture us as we move through our lives.

During and long after periods of toxic stress, the stress responses are activated more frequently and for longer periods than normal or necessary. The stress response will engage at lower thresholds to events that might not be stressful to others. And because the brain and body are so deeply, inextricably connected and reliant on each other, the effects are wide-ranging and profound. Without support, children who experience toxic stress are set up for developmental, neurobiological, health, and relational problems.

Lifelong Effects of Toxic Stress & ACEs

In humans, 80 percent of brain development occurs in the first four years, meaning these years largely influence whether a child will experience the lifelong effects of toxic stress through adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). There are additional bursts at adolescence and in early adulthood, but the foundation — for verbalization, logic and emotion processing, empathy, everything we rely on to function in a complex society — is laid before the age of five.

Adverse childhood experiences disrupt this development, which leads to social and emotional cognitive impairments that make healthy relationships — the only true antidote to stress — difficult, perhaps impossible. This in turn can lead to the adoption of health-risk behaviors that can result in disease, disability, social problems, and even early death. The lifelong effects of toxic stress must be researched and addressed with evidence-based prevention and interventions.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study, organized by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente, has been tracking young participants into adulthood, collecting data about their health and the lifelong effects of toxic stress, since the late 1990s. The findings have been staggering. In 2007, a report published in the Journal of Integral Theory and Practice noted that “research … strongly implicates childhood traumas, or ‘adverse childhood experiences,’ in the ten leading causes of death in the United States.”

The report continues:

“History may well show that the discovery of the impact of ACEs on noninfectious causes of death was as powerful and revolutionary an insight as Pasteur’s once controversial theory that germs cause infectious disease. His ideas were slow to be adopted, but are now universally accepted. Similarly, ACEs parallel what Pasteur offered—an underlying syndrome implicated in noninfectious causes of death. This is truly a remarkable discovery that is likely to change the way in which the field of medicine is viewed and practiced.”

Larkin, et al. 2007

For more on this, watch or listen to the March 2019 City Club presentation by California Surgeon General Dr. Nadine Burke Harris, a pediatrician and leading advocate for addressing ACEs and the lifelong effects of toxic stress.

The Difference Between Toxic Stress & Trauma

It’s important to distinguish between toxic stress and trauma. They can be related, but trauma is, by definition, intolerable. The mind will look for ways to compensate for the pain of a traumatic event, and brain function can be altered.

The response to trauma is most notably different from stress in terms of recollection. We’re all familiar with the way most memories degrade over time. Some things slip away altogether, and other things become hazier and harder to recall. A traumatic event, however, can be seared into your memory in excruciating detail for the rest of your life (for individuals who don’t experience dissociation or other trauma-related memory lapses). This is because of the way the brain is activated at that moment. That is a core component of a traumatic experience.

Toxic stress may not have any flashbulb, incidental memories attached to it. Memories of stress resulting from neglect, abuse, poverty, racism, and other toxic stressors may become less vivid later in life if circumstances change and relational capacities improve.